It’s been a long haul, but progress is now underway on implementing recommendations made in the review into Britain’s dependence on what is often described as an “invisible utility”. Andy Proctor takes up the story

When I left industry in 2013 to join a Government agency (the Technology Strategy Board, now InnovateUK, the UK’s Innovation Agency), one of my first phone calls was from a colleague at the Ministry of Defence who asked, “When are we going to get started on this Position, Navigation and Timing (PNT) group we have talked about?”.

It started me, many colleagues and, ultimately, the UK Government, on a path that is still unfolding: to raise the awareness of how PNT is really used in critical services such as financial transactions or energy systems; and how to ensure that the UK has access to the PNT data it needs to deliver critical services, under all conditions, expected or unexpected.

This article describes the Blackett review into the dependency of the UK’s critical services on Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS)1,2, its recommendations, and how the need for PNT resilience is now being addressed within central government.

Prior to Blackett, an informal “cross-government PNT working group” concentrated its efforts on sharing information about what departments were doing, identifying common areas of interest, discussing new technologies, and joining up interested parties. Its membership was the collective “brain trust” for PNT across Government and regularly attracted more than 25 individuals to its meetings. The group addressed topics across the PNT sphere, from atomic clocks to space systems, and from radio navigation to projects that investigated new tools for celestial navigation.

Assessing the risk

In 2016 two reviews were conducted; a Blackett review into the opportunities that quantum technologies could offer to the UK3, and the London Economics review into the financial impact of the loss of GNSS to the UK economy, commissioned jointly by Innovate UK, the UK Space Agency and the Royal Institute of Navigation, and published in 2017.4

The recommendations of these reviews spurred the Government Office for Science, led then by Sir Mark Walport, to consider PNT aspects of GNSS and if we had unmet/unknown dependencies. In making several recommendations, this Blackett Review of UK Dependencies on GNSS, published in 2018, revealed that:

- awareness of GNSS is out of step with dependence,

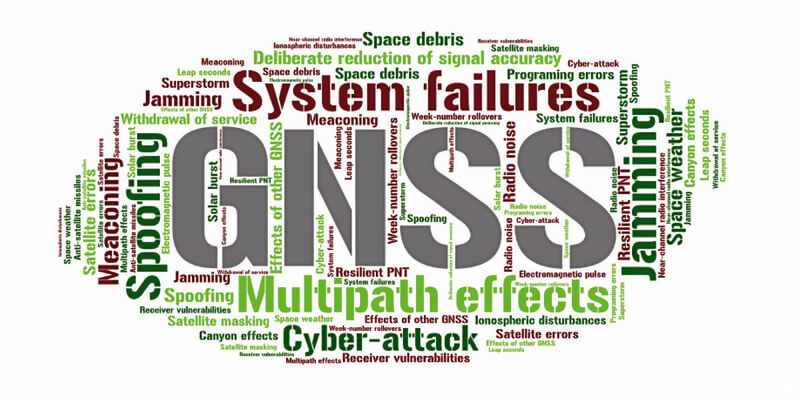

- knowledge of vulnerabilities and weakness of GNSS is not widespread enough,

- resilience improvement is needed across all critical services (such as Critical National Infrastructure) including philosophy of approach. There is no magic single solution,

- we must prepare now for future technologies, skills and product needs to secure future PNT services,

- we must protect spectrum and address risks and interference issues,

- have a formal internal (government) advice system and deploy GNSS backup systems where appropriate,

- address common terminologies, procurement approaches, legislation and

- the UK is well placed globally to actually do something about it.

Addressing the issue

So, what has been done to address these findings? One of the first steps taken by the Government was to form a group to assess the feasibility of implementing the recommendations. It is unusual for the Government to respond in this way to a Blackett review, but the subject matter was taken extremely seriously by organisations such as the Cabinet Office.

The newly-formed Blackett Review Implementation Group (BRIG), with members drawn from the cross-government policy area, focussed on legislative and policy aspects arising from the review. The BRIG was chaired by a Cabinet Office Deputy Director and reported up through the UK’s National Security frameworks. In addition to the BRIG, the former cross-government working group was reformed into a formal technical advisory group (a recommendation of the Blackett review itself). The membership was similar to its predecessor but now included representatives from industry and academia.

Many of the recommendations were assessed and indeed addressed, improving the awareness of the use of PNT by reporting requirements within the Sector Security and Resilience Plan5 process; understanding the current and future threat to PNT based systems, and understanding the role of existing legislation in combatting these threats. In addition, InnovateUK, now part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), completed the PNT facilities study and UKRI analysed R&D options, both recommendations from the Blackett review.

Test facilities

The PNT facilities study concluded that the UK has a range of PNT test facilities with good coverage of PNT technology types and domains. These facilities are owned by a balanced mix of public bodies, academia and private entities, with the vast majority (77%) being available to third parties. It noted, however, that the coverage is limited for Timing and Synchronisation (T&S). The study identified that future needs in the testing space should cover additional types of GNSS simulation, 5G and other communication PNT hybridisation and application-level testing.

The UKRI analysis has resulted in several new submissions for funding to various Government and European Space Agency support mechanisms. Some of these submissions have moved to projects and towards commercialisation.

At the same time as the BRIG and its technical advisory group was working on solutions to the issues raised in the Blackett Review, Brexit was also focussing Government minds. The widely reported Operation Yellowhammer came into force, and many of the teams engaged in the BRIG were redeployed. The result was that all specific activity on the Blackett Review recommendations was paused.

Increased awareness

Another programme also started up around the same time, that of the UK GNSS concepts assessment programme. This programme was created to investigate the UK’s options for an assured/secure GNSS in the absence of the ability to use the EU’s Galileo Public Regulated Service (PRS) capability. This programme has also increased awareness of the need, use of and the dependency on PNT, whether space-based or not.

A combination of these factors, plus better knowledge of the threat environment, led policy makers and senior civil servants to propose and implement a new structured method to analyse the UK’s PNT requirement in the post-Yellowhammer “back to normal” environment. This is another major step forward in how PNT is viewed in the UK Government. The sponsor is the Deputy National Security Advisor as the “Government PNT Authority”, now combined with a steering group and a strategy group.

The strategy group can be considered the delivery function for the steering group. This enhanced focus on the understanding of the PNT need across Government and critical services, means that for the first time, full time resources are deployed on the problem pulling support from specialists where appropriate. The structure including the sub-groups are shown below.

Capability audit

The initial tasking is similar to that of a capability audit. Identifying the use cases for PNT; assessing the technologies currently in use and available in the future; measuring the reliability of these in the known threat environment; identifying gaps, and the credible options for filling those gaps. There is also a particular emphasis on understanding how to deliver awareness, skills and for education and training that will ensure the findings of the main body of work are understood and prioritised appropriately.

This audit will produce the following outputs:

- An assessment of the UK’s requirement for PNT services

- A draft PNT strategy

- A consolidated threat and hazard report

- Assessment of the skills and training aspects of PNT in the UK with recommendations

- Identification of current and future technologies able to address capability gaps

- Assessment of the programme and investment opportunities that are identified from the analysis

The reports are likely to be available in 2020, and the question of public release addressed once all the available information is analysed and the sensitivity relating to the UK’s infrastructure assessed.

This is, indeed, positive news for all those involved in PNT in the UK. It is an example of proactivity within Government, although some may say it has been a long time coming. Ultimately the issue of PNT, resilience and vulnerability has now got the senior backing, focus and tasking for which many calling since the 2010 Royal Academy of Engineering report6 that investigated our reliance on GNSS and its associated vulnerabilities.

1 A Blackett review is process for government to engage with academia and industry to answer specific scientific and/or technical questions. The process can provide fresh, multi-disciplinary thinking in a specific area. In each review, a small panel of 10-12 experts is tasked with answering a well-defined question or set of questions of relevance to a challenging technical problem.

2 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/satellite-derived-time-and-position-blackett-review

3 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/quantum-technologies-blackett-review

4 https://londoneconomics.co.uk/blog/publication/economic-impact-uk-disruption-gnss/

5 SSRP process is a process used within Government to create plans setting out the current level of infrastructure risk. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sector-security-and-resilience-plans-2018-summary

6 https://www.raeng.org.uk/publications/reports/global-navigation-space-systems

Andy Proctor is Technical Director (GNSS) at the UK Space Agency in Swindon, Wiltshire (https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/uk-space-agency), and Chair of the Positioning, Navigation & Timing (PNT) Technology Group.