Nearly 20 years after the Marrakech declaration, Holger Magel and Uchendu Eugene Chigbu look at why the urban-rural divide is still increasing around the world and what must be done to end it.

In 2003, FIG and partners including the UN-Habitat, UNECA, UNEP, FAO and the Arab Federation of Surveyors committed to putting the topic of ‘Urban-rural interrelationship for sustainable development’ into action for the betterment of everyone in the world. This commitment was the ‘Marrakech Declaration’, which sought to raise awareness of urban- rural interrelations for an improved world by tapping into the close linkages urban and rural areas share. Nearly 20 years later, the issues have evolved, but the problem remains with us. Many interested stakeholders have been part of the urban-rural partnership debates over this period. They include those from activism, humanitarianism, policy administration, practice and businesses backgrounds. Many talks have been given and thousands (if not millions) of papers have been written on this issue. It has become more urgent than ever in the light of the ongoing or ever-increasing urban-rural divide around the world, even in rich and poor countries of the world. Why does this still happen despite the many beautiful papers and promising policies that have been produced?

States of mind

A look at the thinking behind urban and rural development shows that efforts have been made to ignore rural development. The state of the urban-rural divide observed today reflects the states of mind of those who determine the course of action.

For instance, big businesses (such as Amazon, Microsoft, Apple and Google) have embraced agglomeration economies – the benefits firms receive from co-location or concentrating their economic activity in one place. These corporations believe they must site their businesses in cities, ignoring rural areas.

In the minds of jobless people who hope for better employment, it is best to abandon the rural areas and head for the cities. This false hope leads to the growing experience of informal settlement lifestyles and urban poverty.

It is also in the minds of all those whose thought processes align to only an urban world. These people think only about the urban. They even question why a government should invest money in rural areas with little or no economic returns. They forget a natural reality –a city cannot physically and socioeconomically exist sustainably without the land resources of rural areas.

What about the minds of the politicians? Most of them lack an understanding of what rural areas mean to the heritage of their nations. Even the ones who have some knowledge of this most times officially fight for the development of liveable rural areas but still support liberal or wrong development policies that enable big companies to site themselves only in metropolitan areas. Over the centuries, this kind of development mindset has led to a downward slope in the development of rural areas (see Figure 1).

All these states of mind contribute to urban problems, such as scarce and

expensive housing, increasing poverty, poor traffic, heat islands and loss of urban green

areas. They also contribute to many rural

problems, such as ‘hollow’ villages (loss of

land resources and decreasing population

in rural areas), neglect of rural infrastructure

and ageing populations. Unfortunately, the

application of these powerful states of mind

in development practices has led to the

manifestation of three spatial worlds – one

that is socioeconomically divided into thriving

urban areas, semi-thriving peri-urban areas

and declining rural areas. Without changing

this state of mind, humanity will be doomed

to perpetual unequal development.

Changing states of mind

Many academics, land practitioners and international development organisations have convinced the world that urbanisation is unstoppable. So, we must embrace it or live with it. They argue that 70% of humanity will live in cities by 2050.

Does having about 70% of the world in cities mean that we must be an urban world? Not necessarily! Today, Germany has an urbanisation rate greater than 70% yet is considered rural because more than 80% of the land in the country belongs to rural areas. Do you see why we must work on our state of mind? The idea, notion or concept that when the rural changes, it is no longer rural, but the urban remains urban even if it keeps changing in demography and physical attributes should be regarded as poor thinking. Change is a natural phenomenon, not a special preserve of the urban. Rural areas change, and rural people change too.

It is time to start a new urban-rural partnership in the urban surroundings but on the fringe and rural hinterland. This should be a matter of solidarity and mutual respect. It should be the task of states and based on territorial development policies that adhere to fundamental, indispensable values of each society. Rural areas should become a place for rural jobs and not merely offer life support to urban areas.

Hence, building modern infrastructure in rural areas to keep rural people in their homes and discourage them from moving to cities should be a priority. Introducing shared urban-rural activities as a matter of intercommunal or regional cooperation should be made policy priorities for urban-rural co-existence and co-development. These should be spatial partnerships based on a principle (and practice) that there is no hierarchy between urban and rural areas and that all areas are dependent on each other. This means aspiring for equivalent living conditions.

New states of mind

Renewing the current states of mind on urban-rural development requires embracing methods and instruments for the urban- rural continuum or even cooperation between urban centres and rural regions. The territorial justice aspect revolves around adapting two fundamental principles of justice, which can lead to a just society. These two principles entail ensuring that members of societies enjoy fundamental liberty compatible with those enjoyed by others. And second, guaranteeing that socioeconomic positions are to everyone’s advantage and open to all who seek it.

Territorial justice presents a logical justification concerning why equivalent living conditions in urban and rural areas should be a critical objective of all spatial development models. Together, urban-rural linkages and territorial justice are factors for equal development (see Figure 2). However, this responsibility is on all of humanity.

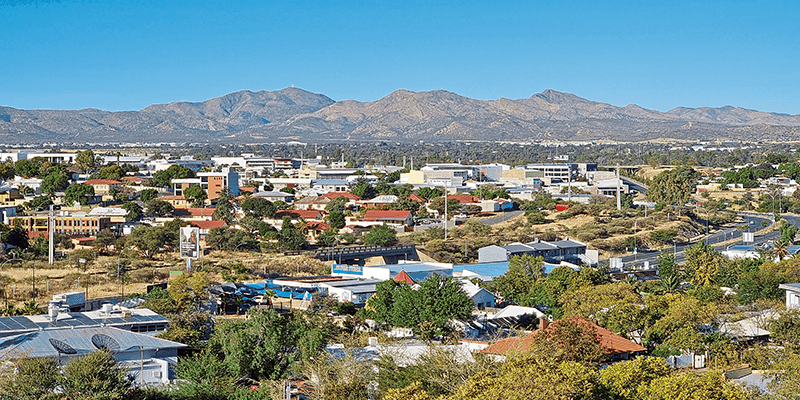

Holger Magel is FIG honorary president and emeritus of excellence professor at the Technical University of Munich, Germany. Uchendu Eugene Chigbu is an associate professor in land administration at the Namibia University of Science and Technology, Namibia