Drones are now in worldwide use for inspecting utility towers and bridges, air transport infrastructure, railways and roadways, and much more. They can be operated at a fraction of the cost of traditional inspection crews, and, when equipped with the latest technologies, such as LiDAR, state of the art GNSS and inertial sensors, they can deliver the highest quality in imaging and positioning data.

For an idea of what’s being done in the infrastructre inspection area, we begin with Bart Zondag, the very big president of the very small Netherlands-based company GeoInspect. In June 2018, he took his kit to the Dutch Caribbean island of St. Eustatius to inspect the local air transport infrastructure.

Back in 2017, St. Eustatius was hit hard by Hurricane Irma, especially at its eastern edge, where the island’s airport is located. “In the absence of a proper marine port, the airport is really the only practical means of getting numbers of people and cargo on and off the island,” Zondag explained. “The single airstrip is situated just a few tens of meters from the edge of a coastal cliff, which had been severely eroded during the storm.” GeoInspect’s job was to go in and assess the threat to the airstrip posed by this damage, focusing on some newly formed ‘gullies’ in the cliff.

“Most of these Caribbean islands are no-fly zones for drones,” Zondag said, “but because this airport is so important to St. Eustatius, and after some lengthy discussions, we got the permission to come in and fly.”

Zondag knew that such a small and remote island might be lacking in other kinds of infrastructure, for example cell phone networks. “So, we took with us an old-style, air-frequency radio, so we could talk directly to the airport control tower. They were very helpful; they coordinated with us and other aircraft throughout the project. They don’t exactly have Boeing 737s or 747s landing; it’s small planes that come in once in a while.”

The detailed LiDAR scan of the gullies was done using a pretty standard setup—a DJI M600 multi-rotor drone with an Applanix- and Velodyne-equipped YellowScan Surveyor LiDAR module. (See “Hardware Highlight: YellowScan Surveyor,” left.)

The majority of YellowScan’s customers fly the DJI Matrice 600. It’s not too expensive, all things considered, and is very reliable, delivering smooth trajectories and stable flight, and can work in winds of up to 40 kph (25 mph).

“While we were there, we decided to go ahead and do photogrammetry of the rest of the island, using a small fixed-wing drone,” Zondag said. The entire job, including imaging of the island’s massive, dormant volcano, was completed in less than a week.

Zondag, who was one of many informative speakers at the “LiDAR for Drone” conference in Montpellier, France, this March, presented some very impressive LiDAR-generated point clouds showing extremely detailed imagery of the cliff faces near the airport. “You can slice out parts of this and really see how precise it is and how useful it is,” Zondag said. The collected data now serves as a baseline, he explained, for comparisons with future surveys. “With our software tools we can easily load data from two different surveys and compare them to see any changes over time. So you can then calculate how quickly this erosion could turn into a problem for the airport. Will it be in the next five years or in the next hundred years?”

In fact, the GeoInspect team made an interesting discovery, and may have helped engineers permanently solve the problem of the threatened airstrip. “Originally, we all thought this damage had been caused by heavy seas smashing against the coastline. But what we were able to see with these images is that it was actually the rainwater running back down the side of the volcano and flowing toward the sea that was causing this damage. The runoff is not canalized, so it just flows down to the sea any way it can get there, and with the amount of rain dropped by the hurricane, it created these huge gullies.”

With this knowledge in hand, a local engineering company has set out to create a new system of culverts and canals, “and we Dutch are very good at building canals,” Zondag said. “So, they are diverting the rainwater in a different direction now, away from the airstrip, away from the cliffs and we hope this is going to stop the deterioration.”

DRONES ALL OVER

GeoInspect was only one of a number of companies in Montpellier outlining recent infrastructure-related drone missions. Brian Soliday, chief revenue officer of Golden, Colorado-based Juniper Unmanned, laid out to a rapt audience a number of such missions.

He said Juniper likes to work with the Altus ORC single-rotor drone, particularly because of its ballistic parachute safety feature. “We run our YellowScanVX-20 LiDAR with dual-headed, dual collect Sony Alpha A6000 cameras,” he said. “So, when we have this bird flying you can be talking over a quarter of a million dollars of investment in the air. We feel a lot better with that parachute ready to deploy if anything goes wrong. Juniper also runs the DJI M600, and they use Trimble GPS bases and rovers. (See “Hardware Highlight: Altus ORC2,” left.)

One recent Juniper mission was undertaken in Lubbock, Texas, where local authorities were struggling with their own stormwater management issues. “They had water feeding into laterals feeding into a 90-inch main,” Soliday said. “That’s a big sewer line, moving a lot of sludge. The customer wanted long corridor profiles. Our competition was using conventional survey methodology, and they could not even come close to us in terms of time and cost, so we got the job.”

The project involved working in an urban environment, in heavily populated areas: i.e. collecting data in residential neighborhoods, over traffic, parks and people. “One area we were able to image had been recently flooded and the surface was caked with dirt and weeds,” Soliday said.

Flying over urban areas of course implies special permissions. Soliday said it helps if you can show authorities a number of projects you’ve worked on and a list of previous authorizations.

And as long as you’re in the air, why not gather all the additional data you can? Soliday explained: “We did another survey in Yuma, Colorado, where they wanted imagery for a small part of the city. Once we had the permission, we went ahead and did the whole city, because we knew that they would eventually want the rest. We also knew that there was another road infrastructure project that was going to be coming right through there, so we’ll be able to sell this data two or three times. That’s a positive thing, to be able to sell the same data over and over. The Yuma customer only needed digital terrain models, but we did orthographics to be able to sell that later too.”

Soliday pointed out some of the limitations of LiDAR (which made everyone at the LiDAR conference a tiny bit uncomfortable). Working in winter can be problematic, he admitted, because you need the right kind of light to do orthography, while winter means limited daylight and bad angles. And then there’s that fluffy white stuff; during one project in South Dakota, he said, “It was cold and we had snow on the ground. If there’s heavy snow, we’re not going to go out and collect because the LiDAR doesn’t go through snow, while photogrammetry is not going to get but just the top of the snow, so you’re not going to get an accurate terrain model. You might need to go back to the old stake-in-the-ground method.”

There are other solutions. Latvia’s SPH Engineering (they know a little about snow in Latvia) uses a ground-penetrating radar (GPR) unit mounted on our old friend the DJI M600, enabling imaging through snow and ice and even through the surface of the ground, not to mention freshwater and buildings. (See “Hardware Highlight: SPH GPR,” below).

Still, LiDAR remains one of the most powerful and versatile imaging technologies around. Just ask the autonomous car people. And of course, drones are here to stay. That’s something more and more companies and organizations are taking to heart.

As Soliday said, “We do projects, but we’re also seeing more and more of our customers moving to internalize drone operations, so we’re kind of pivoting a little bit. We’re now actually going in and helping them set up their own UAV test organizations, their own UAV divisions. We can help them to define standard operating procedures, their health and safety measures, all the processes that they need to put in place to actually go out and fly safe and effective missions for themselves.”

The venerable Lewis Graham is president at GeoCue Group. We asked him if he’s also seeing companies bringing drone operations in house. “Yeah, for sure,” he said. “Our company’s been around since 2003 and we do a lot of work in manned, airborne, LiDAR, mostly on the software side. We entered the drone market in 2014 when people were just kicking tires and that sort of thing. We work a lot in mining in the U.S. and we’re seeing larger companies, they’re doing the math and saying we might as well try internalizing this and do our own department. We’re talking about service providers such as traditional surveying companies that more recently may have started contracting some drone services,” Graham said. “They’ve started to bring that stuff in house.”

Is this a sign of acceptance? “Absolutely,” he said. “We saw the same thing many years ago with the tripod laser scanners, where people contracted it out and then as soon as they contracted out 10 jobs they said, ‘Look how much money we’re paying, we could have bought our own scanner by now.’”

NEXT GIANT LEAP?

The outlook for the drone-as-infrastructure-inspector is still unclear, Graham said. “It’s amazing to me that there’s only one company in the world that makes a laser scanner focused on mapping for drones, which is RIEGL. There are a number of companies that have it for manned aircraft, but not for drones. RIEGL is the only company that even builds a LiDAR. Everything else is re-purposed automotive stuff, like Velodyne for example. Trimble, which builds ground-based, terrestrial laser scanners, and also Leica, have yet to introduce scanners for airborne drones. So, I think that’s an indicator that we’re still early in the market.”

Should we be looking to an outsider to make that move? Graham said he knows of probably two dozen Chinese laser scanner manufacturers active right now, “but everybody’s after automotive, because the numbers are so large. You know drone mapping, how many are you going to sell in a year compared to what you could sell in automotive?”

While we’re on the subject of RIEGL, we can mention Philipp Amon’s presentation. In his role as the company’s business division manager, he described a range of RIEGL LiDAR products for the unmanned sector, from the popular miniVUX-1UAV to the miniVUX-1DL with downward-looking scanner.

“The main thing when you talk about unmanned is the weight,” he said. “The miniVUX weighs just 1.55 kg while big brother BDF-1 is up to 5.3 kg, with a corresponding step up on many performance characteristics. Our top-of-the-line scanners deliver in the range of 1000 data points per square meter. That’s a lot!”

Amon went on to describe a number of infrastructure inspection projects that have been undertaken by RIEGL, including a recent power line substation survey. “LiDAR is perfectly suited for this,” he said. “Photogrammetry is not as good by itself, but for us the key is the combination. If you can do photogrammetry combined with LiDAR, this gives you really a great tool.”

We note here RIEGL’s interesting position as both a supplier of LiDAR components to technology integrators and drone service providers, such as YellowScan, and as a drone service provider itself, with its own line of innovative airborne platforms, including the impressive RiCOPTER.

Petter Hoffman, regional manager at TRIMTEC, also believes in the power of combining multiple sensor systems. “We do resell of Trimble GNSS products in Sweden, and a lot of our customers are using UAVs for infrastructure projects,” he said. “Some projects, in particular road infrastructure, are covered very well with photogrammetry and LiDAR.”

Pipelines are also of crucial interest in Scandinavia. “The Norwegians have a lot of oil,” (Swedish) Hoffman said, with a smile. “This is similar to power lines inspection, where you have these very long corridor projects. Those are very well suited to LiDAR. In the case of power lines of course they are very thin, so you can get that with LiDAR with just a single flyover. With something like pipelines, I think that what we’re going to see is development where you combine different kinds of sensors.

“You create the point cloud with the LiDAR and then you colorize it with an infrared camera, for example,” Hoffman continued, “which gives you a three-dimensional heat image, which would then for example give you the ability to find leakage and so on in heating pipes.”

PUSHING THE RIGHT BUTTONS

Director of airborne products at Applanix, Joe Hutton, said the drone inspection market, “is still in its infancy. The technology still needs to be exploited for all types of applications. These companies today are pretty good at using drones with cameras or LiDAR, but I think what’s really going to open it up is someone to completely automate that drone. You push a button and it goes, surveys by itself, knows how to do it itself, and it comes back.

“What’s holding that back I still think is the software. The hardware’s there, it’s really getting the software so it can control the drone, so it can automate the drone and pull all the data in and do it fully automatically. And even the software, it’s just a case of doing it. You take a look at what’s being done on autonomous vehicles in terms of SLAM [simultaneous localization and mapping] and all that. That’s all going to be done on the drones too. The technology’s there, and the software is doable. It’s really about how it’s scaled for large adoption.”

Ontario-based Applanix designs, manufactures, sells and supports inertial-aided GNSS technology for georeferencing images sensors on land, in the air and at sea. The industry standard for mapping from manned aerial platforms, Applanix offers an extensive product portfolio for the unmanned sector as well.

Hutton said Applanix, a Trimble company since 2003, is continuously reinventing itself in its drive to stay ahead of trends. “We brought GPS inertial into airborne mapping. We started on cameras, got into LiDAR, and then we took it into mobile mapping and onto marine applications.

“We saw UAVs coming up and said, ‘Hey, there’s an opportunity there.’ For us, it was another platform that moves and we needed to map from it. How did we do it? We had to disrupt and develop new inertial technologies and get them onto this platform.

“That’s what we do, and that’s one of the reasons why Trimble keeps us as a separate entity, so that we can continue to be lean and mean and disruptive. And then we take our technology and push into the rest of Trimble as well.”

THE SAFE WAY FORWARD

It may still be early days for drone-based infrastructure inspection, and, in the future, we may well look back on these days and remember clumsy and quirky operating procedures and complicated data processing. But drone operations, as they stand, make obvious sense right now, and they are rapidly being embraced around the world. Leading companies such as Microdrones are delivering complete, integrated, unmanned aerial systems for inspecting power lines, cell towers, oil and gas pipelines, and railways.

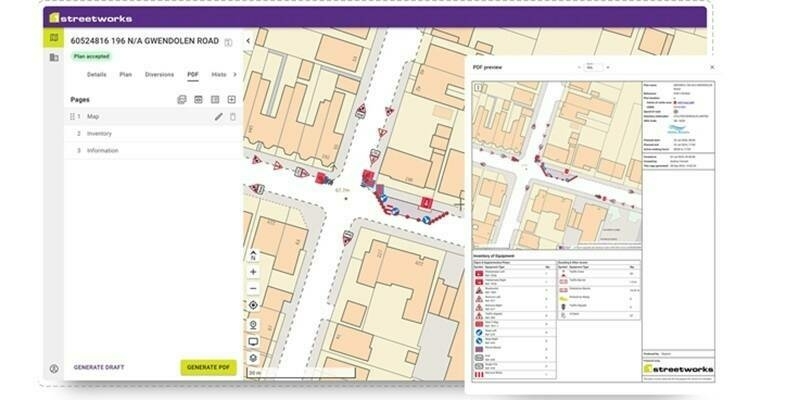

Large and complex structures are best surveyed from the air and significant savings in terms of time and costs are clearly demonstrable. Also, any number of presenters at the Montpellier event pointed to important improvements in terms of safety, especially in the context of road inspection and planning, where old-fashioned ‘boots-on-the-ground’ surveying puts staff in harm’s way literally on a daily basis. The use of drones for such projects can drastically reduce the risk of accidents and the potential costs and inconveniences caused to local communities.

One UK-based company that has come in for some media attention in recent months is taking its safety procedures to another level. Balfour Beatty uses drones in infrastructure inspection operations, including on bridges, roads and railways, as well as in support of its engineers and architects on work sites. To maintain the highest safety standards, the company actually flies drones in tandem, with a primary drone undertaking specific duties related to the project at hand, while a second, camera-equipped, drone monitors and records its actions.

The bottom line of course comes back to the customers’ happiness. Here, the last word goes to Juniper Unmanned’s Brian Soliday. Speaking about the Lubbock project, he said, “We flew for two days and the customer was incredibly ecstatic with the deliverables.” Case closed.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay updated on the latest technology, innovation product arrivals and exciting offers to your inbox.

Newsletter