PhD candidate uses professor’s hand-drawn data to track the resilience of songbirds

Miranda Zammarelli, Guarini, was a graduate student at Dartmouth for just nine days when her interests in birds, history, and archives converged in a set of old filing cabinets in New Hampshire's White Mountains.

She had spent the first days of June 2021 brainstorming projects with her adviser, Professor of Biological Sciences Matt Ayres, as they explored a 25-acre area within the long bowl-shaped valley of the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest that is reserved for studying birds.

But it was in the main building at Hubbard Brook, about a 60-mile drive northeast of Hanover, that she was shown a store of hand-drawn paper maps for every year since 1969. The parchment-thin maps were the work of Richard Holmes, now an emeritus professor of biological sciences, who for more than 50 years led students into the forest for several weeks at the peak of spring breeding season to document the territorial boundaries of songbirds by listening for their distinctive songs.

"One word: Amazing," says Zammarelli, who as an undergraduate at the University of Rochester worked as an archives clerk in its special collections library. "I love history and I love data, and I was in awe of all these data."

Zammarelli started working with Holmes to digitize and preserve the maps, leafing through pages adorned with the dates that two generations of Dartmouth students—many of them older than her parents—used to mark when and where they heard a song.

Sometimes, when a male bird sings, a nearby male of the same species sings back, creating "territorial rap battles" that reveal who is holding what ground and where the boundaries are, Zammarelli says.

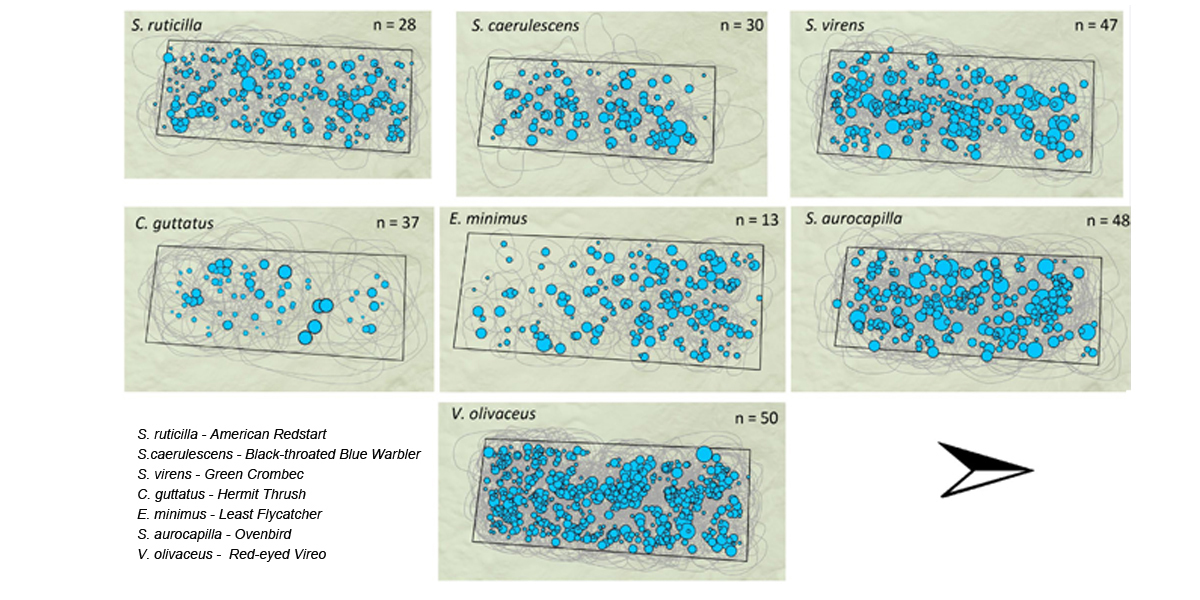

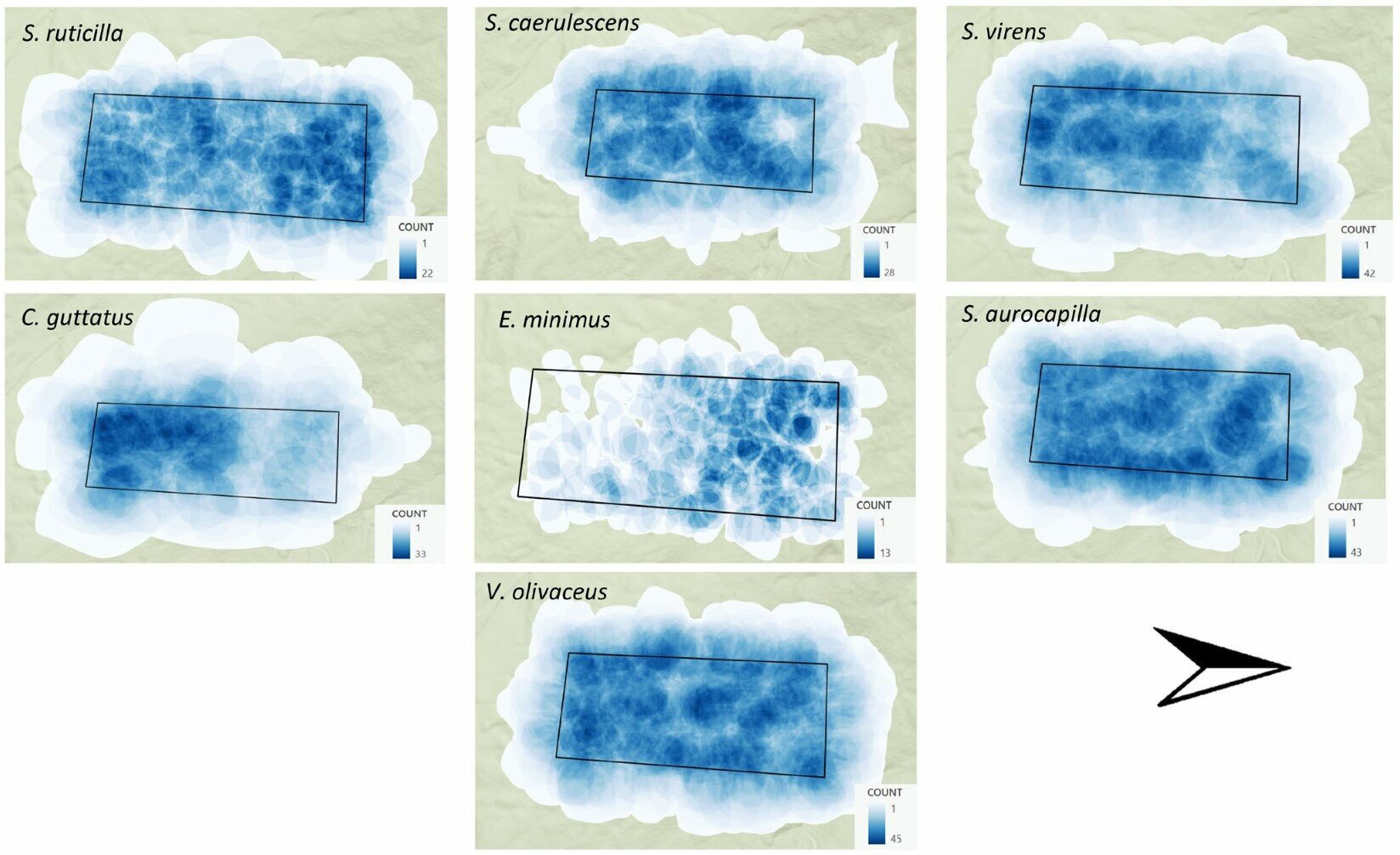

Circles on maps

Holmes and his students created maps from those songs by layering the thin sheets over one another until they could see the locations of the territories of each species for the entire season. Circles drawn around the clusters of dates show where mated pairs of each species had staked a claim. The hand-scrawled numbers thin toward the edge of each circle, beyond which lay the border of another circle and a different pair's turf.

"I spent two weeks digitizing maps and thinking about the questions we could answer with these data," Zammarelli says. "It's amazing what 8 hours a day in front of a scanner will do for your thinking."

She noticed that over 50 years, the size of the circles changed with the abundance of birds on the plot. The maps showed that territories shrank when the population was high and expanded when it was less so.

But individual species showed a stable preference for certain parts of the forest over others, with their territories clustered in specific habitats regardless of the surrounding population abundance. A few species disappeared from the study plot as the forest aged and the available habitats changed.

"We would not know what these birds' preferences were without this data set," Zammarelli says. "Long-term data helps us account for environmental variation over time and allows us to know if individuals have preferences for certain spaces, even as the surrounding environment changes."

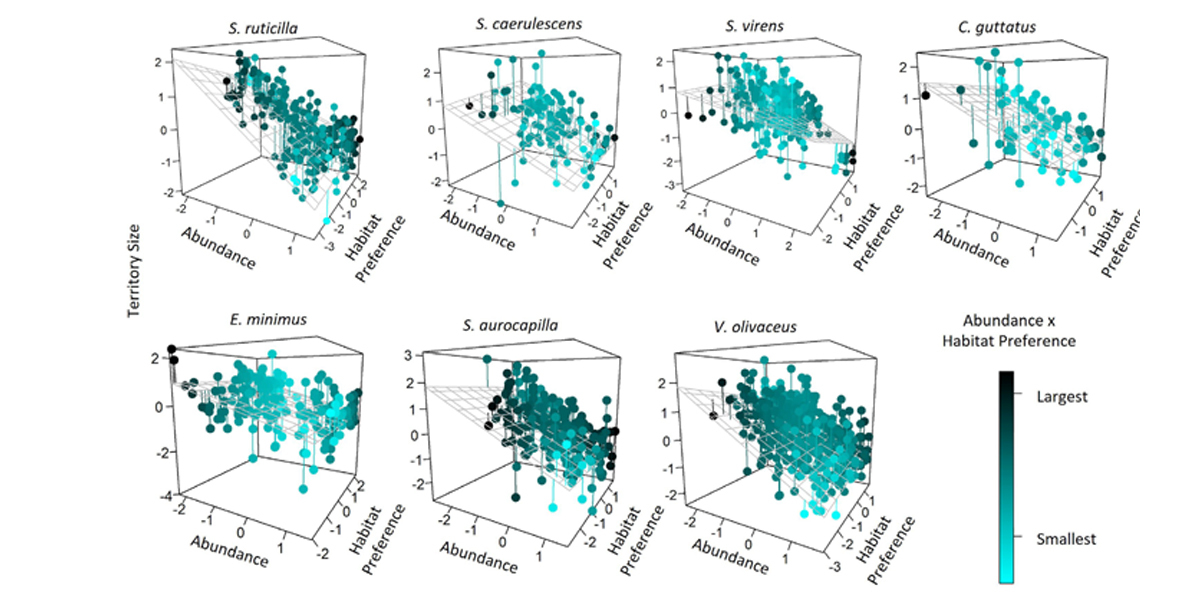

That observation resulted in a recent paper Zammarelli published in Ecology Letters with Holmes, Ayres, and other Dartmouth researchers suggesting that the multitude and ubiquity of songbird species may be related to this ability to hold defined but flexible territories that adapt to population pressure.

Three songbirds in the Dartmouth study—least flycatcher, black-throated green warbler, and red-eyed vireo—as drawn by Raisa Kochmaruk of the Hubbard Brook Research Foundation. Credit: Animation by LaDarius Dennison

Zammarelli conducted spatial analysis on the digitized maps with David Lutz, Guarini '23, an assistant professor of environmental science at Colby College, and Hannah ter Hofsted, a past Dartmouth faculty member who is now an assistant professor of integrative biology at the University of Windsor in Canada.

The study, led by Zammarelli and Holmes, focused on the seven most abundant species in the Hubbard Brook tract from 1969 to 2021: black-throated green warbler (as pictured in our lead image), red-eyed vireo, American redstart, ovenbird, black-throated blue warbler, hermit thrush, and least flycatcher.

The researchers found that average territory size could vary by three to 11 times from year to year depending on the species and overall abundance. The abundance of a particular species could change by multiples ranging from two to as high as 22.

For example, American redstarts swung from holding a whopping four acres of territory when there were five pairs in the Hubbard Brook study plot to less than one acre when there were 21 pairs. Also, territory sizes were surprisingly variable—up to double—for neighboring pairs of the same species in the same habitat in the same year.

Theory of ideal free distribution

The findings relate to a long-standing interest among ecologists in a theoretical model known as the ideal free distribution. Also known as IFD, it is one of two competing theories of how territorial animals respond to population pressure. IFD contends that animals organize into uniformly smaller habitats as the overall population increases.

Its alternative, the ideal despotic distribution, or IDD, suggests that the territory size of dominant individuals remains unchanged when populations are high while subdominant birds are pushed into smaller territories and/or unsuitable habitats.

"Birds are less prone to population decline as a consequence of following IFD," Zammarelli says. "They are distributing themselves in a way that promotes equal fitness across high- and low-quality habitats, despite changes in population size across years. Under IDD, the few birds in high-quality habitat reproduce successfully, while many others are forced into low-quality habitat where they are less likely to be successful."

"Birds are so good at distributing themselves based on density that it has the emerging effect of stabilizing population dynamics," Ayres says. "How are they so efficient? It's because they can sing. It's easy for birds to know where other birds are around them. Behaving this way is a very favorable scenario because they are less susceptible to environmental vicissitudes."

"Without more than a few years of data, you don't catch natural fluctuations in abundance, and you need that to see how species respond to those changes in population," Ayres says.

Holmes says that ecologists have debated the occurrence of IFD versus IDD since the early 1970s, and by studying the long-term patterns of birds at Hubbard Brook, Zammarelli came up with an answer.

"This is probably the longest set of records of this sort anywhere. We hadn't thought of using it in this way, but it turns out to provide some new and important insights," says Holmes, who is the Ronald and Deborah Harris Professor of Environmental Biology Emeritus.

"The findings probably apply to most forest-dwelling songbirds in these ecosystems," he says. "Most forest songbirds in North America will have similar territorial systems, so, as conditions change, they adjust their territory size to local conditions, and that behavior allows them to maximize reproduction in that particular site."

The researchers developed a general model for determining if bird species—and possibly other animal species—fall under IFD or IDD based on their abundance, habitat preference, and territory size. Their model can be deployed with far less than 50 years of data, Zammarelli says.

"In other territorial animals where this information is known or can be quantified, our model could help conservation organizations decide how to focus their efforts. It can tell them how populations are distributing themselves and if territory size is dependent on the number of individuals there," Zammarelli says.

Importance of habitat

The study shows that animals—or at least birds—that conform to IFD can thrive on a mixture of high- and low-quality habitat, which would greatly help conservation, she says. The focus becomes less on the quality of habitat and more about connecting suitable habitats.

"It's important to know how species are using space," Zammarelli says. "High-quality habitats are still important for conservation, but protecting areas that include less diverse or lower-quality habitat allows for easier movement for individuals across the landscape, especially in years where there is higher abundance."

The project also is the type of hands-on, collaborative research on climate and the environment by students and faculty that Dartmouth is trying to encourage through its new Climate Futures Initiative, launched last year as part of the Dartmouth Climate Collaborative.

Holmes, now 88, still leads students on expeditions to Hubbard Brook each spring to conduct a census of songbirds. Minus the year off for during COVID-19, the project is now in its 55th year.

Zammarelli oversees the mapping, which students carry out with smartphones—first used in 2022—and song-recording devices hung from trees. "All my maps were hand-drawn, so it's quite the upgrade," Holmes laughs. "I'm no longer able to pick out some of the calls, which can be really high pitched. So, I let the young people with good hearing do most of the census work now."

When the project started in 1969, Holmes was studying the role of birds in ecosystem structure and functioning. He was particularly interested in the cycling of nutrients and energy through the food web as leaves consumed solar energy, caterpillars consumed leaves, and birds consumed caterpillars. To address these questions, he had to know how many birds were in the forest and how they were distributed.

"Hand-drawn maps were the only way to obtain territory sizes and population estimates in the '60s and we kept it going because it was the way it was done," says Holmes, who has built on that study during the past five decades. He more recently shifted his focus to the role of climate and other factors that are causing changes in bird abundance, which is relevant to concerns about the recent decline in bird populations.

"I'm happy to have people pursue whatever new ideas they have for these data and to keep this project going as long as possible," he says. "There are a lot more questions to be asked."

More information: Miranda B. Zammarelli et al, Territory Sizes and Patterns of Habitat Use by Forest Birds Over Five Decades: Ideal Free or Ideal Despotic?, Ecology Letters (2024). DOI: 10.1111/ele.14525

Journal information: Ecology Letters

Story Source: Morgan Kelly, Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay updated on the latest technology, innovation product arrivals and exciting offers to your inbox.

Newsletter